In the aftermath of the Cuban Revolution in 1959, one of the greatest challenges was how to educate the population in the ideals and potential embodied by the revolutionary process. Due to the massive inequalities which had prevailed under the Batista regime, many of the population were illiterate, and film was determined to be one of the best ways in which to reach the public and spread the word. Within the Dirección de Cultura del Ejército Rebelde (Culture Division of the Rebel Army) was set up ICAIC (the Cuban Institute of Cinematographic Art and Industry), which still maintains the Cuban film industry and archives to this day. Essentially, ICAIC emerged from a radical pedagogical impulse, initially focusing on documentary, many of which are classics of the form.

The first filmmaker to come to the fore, and indeed become the first Cuban filmmaker to gain international recognition, was Santiago Álvarez, who was one of the institute’s founding members. He was tasked with producing the Noticiero ICAIC Latinamericano, a series of weekly newsreels whose radical form would be dictated by the primitive non-sync sound equipment he was working with, allowing Álvarez to ditch the clichéd omnipotent narrator, and play with a barrage of sound effects.

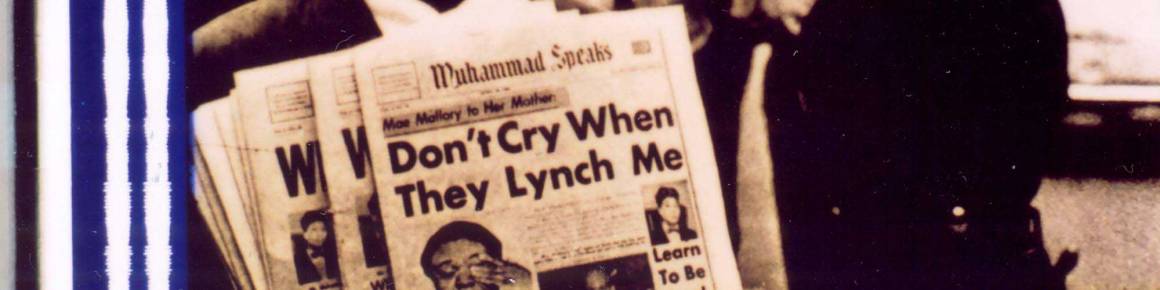

Perhaps ironically, Álvarez would become more celebrated for his films on American political struggles than documenting Cuban issues, in particular Now!. The island has, of course, long had a conflicted relationship with both its larger neighbour, the US, and with race. Fidel Castro claimed that the revolution had ended racism, declaring the island “colourblind”, which was both a difficult process to enact in a country with such a complex colonial history, and a claim that would be contested by the great Afro-Cuban filmmaker Nicolás Guillén Landrián, whose career would be brutally truncated as a result. However, since by the early ‘60s the US was mired in the struggle for civil rights, a battle that has still been far from resolved, this was a relatively open goal for Álvarez. Indeed, for him, it was personal, having escaped to the US during the depression, while his anarchist father was being persecuted by the dictator Batista back home. His further work as a music archivist would be key to this film’s power. Álvarez once stated, “Give me two photographs, a moviola and some music and I’ll make you a film” – that’s essentially what he did here, utilising an incendiary mix of photos and stock newsreel footage depicting American racism, with the bonus that leading African-American singer Lena Horne had given him her song ‘Now’, banned in the US, to use as his soundtrack. The combination of song and dynamic montage of images is overwhelming, in what comes on like some agit-prop proto-pop video, and could be seen to have contemporaneous parallels with the work of Bruce Connor in the States, but far more politically engaged.

Álvarez would hone and develop his style of ‘nervous montage’ in his next attack on the US, LBJ, a brutal satire on the current president, Lyndon B. Johnson, and the regime he presided over. The very sound of the three letter acronym cannot but help evoke those more famous contemporary figures JFK, whose shoes he had to inadequately fill and in whose shadow he would be fated to live, and MLK, Martin Luther King being judged far more favourably than our eponymous subject. The film is structured around L, for King, B for Bobby Kennedy, and J for JFK, Johnson being presented as a lack, a wannabe cowboy or knight, ironically defining him in relation to the Kennedys and King, and coming up sorely wanting. Álvarez once stated, “The advertisements of capitalism are, in fact, much better than the product”; and he gleefully undermines pop imagery with images of the history of colonialism, via native Americans, racism toward African Americans in the country, and the film’s most contemplative passage, celebrating African art, which looks like it’s strayed in from Resnais and Marker’s Statues Also Die. Of course, JFK, MLK and Robert Kennedy would all be brutally assassinated, and the shadow of violence is always lurking here, directly equated with LBJ, and eventually Nazism itself. Musically, the film is equally dialectically structured, with music from artists connected to Civil Rights – such as Miriam Makeba and Nina Simone – contrasted with the ominous pomp and bombast of fascist composer Carl Orff, several years before Pasolini would use Orff to the same conclusions in Salò.

The film ultimately extends the horrors of Johnson’s regime to Vietnam, another own goal for the U.S. as they picked up on France’s doomed imperial project in the country. Álvarez’s most lyrical film, 79 Springs, would deal directly with the subject, in an impassioned tribute to the revolutionary leader Ho Chi Minh, whose death at 79 lent the film its title, and saw Godard hail Álvarez as “the world’s greatest film editor.”

Those editing skills would be tested with Hasta la victoria siempre, which saw Álvarez return to his roots when he was tasked by Castro to produce a film in 48 hours on the killing of Che Guevara. There’s no doubt that Álvarez is the most didactic and propagandistic of the great Cuban filmmakers of the period, which may have led to his relative obscurity today. But in terms of both his technique, which anticipates the current fascination for appropriating archive footage and imagery in artists’ film, and political commitment, when younger filmmakers for whom activism and aesthetics are interlinked are increasingly coming to the fore, he may become an increasingly inspirational figure.

Brian Beadie

Brian Beadie is a freelance journalist and editor based in Glasgow.

Santiago Àlvarez is screening at 18:30 on Sat 26 March at GFT.